Bear Call Spread: Complete Beginner’s Guide

The bear call spread is a defined-risk, bearish-to-neutral trade that profits when the stock stays below a certain level. This vertical spread offers a safer alternative to selling a naked call, but it also limits potential gains.

The bear call spread is a net credit options strategy built by selling a call and buying another further out of the money call, both with the same expiration. I like it because it keeps risk defined, lets theta work in my favor, and doesn’t require a ton of oversight.

Highlights

- Risk: Limited to the spread width minus the credit received — max loss occurs if the stock finishes above the long call strike.

- Reward: Capped at the credit received — max profit happens if the stock stays below the short call.

- Outlook: Moderately bearish or neutral — best when you expect the stock to stall or drift lower.

- Edge: Works best when IV is high and expected to drop.

- Time Decay: Helps the position — especially as expiration nears.

🤔 New to options? It helps immensely to understand both the long call and short call strategies before jumping into spreads.

Bear Call Spread: Trade Components

Here are the trade components of a bear call spread:

- Sell 1 call option (closer to the money)

- Buy 1 call option (further out of the money)

- Both options are calls

- Both options are the same expiration

Ideally, you put on the trade in one spread called a ‘vertical’ spread, which is the same setup for all bull/bear call/put spreads. This setup is displayed below on the TradingBlock dashboard:

Market Outlook: When to Sell a Call Spread

The bear call spread is a defined-risk, neutral-to-bearish strategy. The ideal outlook for this trade is when you don’t expect the stock to rise significantly before the option’s expiration date.

Here are a few different circumstances where selling a bear call spread may make sense:

- Neutral to Bearish Outlook: If you think a stock will trade sideways or fall modestly, the bear call spread profits from time decay on the short option.

- Defined Risk Preference: Unlike selling a naked call, the bear call spread caps your max loss.

- Income Generation: The strategy allows you to collect option premium up front with a relatively high probability of profit, especially if the short strike is adequately out of the money.

Bear Call Spread: Payoff Profile

Let’s first explore the max profit, breakeven, and max loss scenarios for this trade.

Maximum Profit

When you sell a bear call spread, your max profit is capped at the credit received—and that only happens if the stock stays below the short call strike price through expiration.

Let’s say you sell the 100/110 bear call spread on ABC for $4.00 in option premium. Here’s the setup:

- Short Call Strike: 100

- Long Call Strike: 110

- Net Credit Received: $4.00

- Max Profit: $400 (if the stock stays below $100)

As we can see, our maximum profit is capped at the premium received if the stock falls to $100 or below on expiration. We can see why this trade may not be ideal if you are exceptionally bearish. If you are expecting a significant price drop, you may be better off going with a long put.

Breakeven

To breakeven on this trade, the underlying asset must finish at the short call strike plus the premium collected.

Breakeven = Short Call Strike + Premium Collected

Let’s revisit the 100/110 ABC bear call spread we sold for $4.00:

- Short Call Strike: $100

- Premium Collected: $4.00

- Breakeven: $100 + $4.00 = $104.00

.png)

The underlying asset must finish exactly at $104.00 (excluding commissions) for us to breakeven. That’s the point where the $4.00 premium you collected is fully offset by the $4.00 loss from the short call being in the money.

- If the stock finishes below $104.00, you keep some or all of the premium.

- If it closes above $104.00, losses start building.

Max Loss

The max loss of a bear call spread occurs when the stock finishes above the long call strike at expiration.

At that point, both calls are entirely in the money, and your loss is the full spread width, offset by the premium you collected:

Max Loss = Strike Width – Premium Collected

Revisiting our ABC trade:

- Strike Width: 10 points

- Credit Collected: $4.00

- Max Loss: $10 – $4 = $6.00, or $600 per contract

.png)

As we can see, the max loss on this trade is reached when ABC finishes above the long call strike at expiration. If the ABC rises above this price, our gains on the long call offset our short call losses 1x1.

This $600 max loss is also the margin requirment for the trade.

📖 Check out how the bull call spread works here!

Trade Example: XLF Bear Call Spread

In this example, we’re setting up a bear call spread on XLF (Financial Select Sector SPDR Fund).

We chose XLF for a few reasons:

- Broad-based exposure on financials

- Decent bid/ask spreads and low slippage

- Numerous strike prices and expirations

We believe the price of XLF will remain relatively stable over the next 5 weeks while allowing for some upside, so we will target selling a call that is about 5% out of the money.

Let’s jump to the TradingBlock dashboard to find two call options on the XLF options chain that fit the setup:

Trade Details

- XLF Price: 45.72

- Expiration: 39 days

- Sell 48 Call @ $0.73

- Buy 51 Call @ $0.14

- Net Credit Received: $0.59 ($59 total)

- Breakeven Price: $48 + $0.59 = $48.59

- Max Profit: $0.59 ($59 total)

- Max Loss: $3.00 – $0.59 = $2.41 ($241 total)

We’re selling a 48/51 call spread on XLF and taking in a net credit of $0.59. Our max profit, therefore, is $59, and will occur when XLF stays below $48 at expiration.

Our max loss occurs when XLF finishes above $51, in which case we’ll lose the full width of the spread ($3.00) minus the credit received, for a total loss of $2.41, or $241.

Let’s explore a couple of different trade outcomes.

XLF: Losing Trade Outcome

Thirty-nine days have passed, and our option expiration day has arrived. Let’s see how our trade did!

- XLF Price: $45.72 → $53 📈

- Expiration: 39 days → 0

- Sell 48 Call @ $0.73 → $5.00 📈

- Buy 51 Call @ $0.14 → $2.00 📈

- Final Spread Value: $3.00

.png)

Halfway through the life of our spread, XLF tanked, causing our spread to drop to just a few pennies in value. We had achieved over 95% of our maximum profit at that point. It would’ve been smart to simply buy back the spread and lock in the gain, but we rolled the dice… and got run over as XLF rallied hard.

The result was a maximum loss.

- Our long call closed in the money by $2

- Our short call closed in the money by $5.

The result of our spread was a full width of $3.00, leaving us with a max loss of $2.41 ($241 total).

XLF: Winning Trade Outcome

Let’s fast forward 39 days, but this time XLF stayed within our preferred range:

- XLF Price: $45.72 → $46 📉

- Expiration: 39 days → 0

- Sell 48 Call @ $0.73 → $0.00 ✅

- Buy 51 Call @ $0.14 → $0.00 ✅

- Final Spread Value: $0.00

- P/L: Net credit received = $0.59 → Max Profit = $59 total

.png)

The outcome here is almost ideal. While the stock actually rose from where we put the trade on, it closed at $46 on expiration — which was safely below our short strike at $48.

- We bought the 48 call, now worth $0.00

- We sold the 51 call, now worth $0.00

Since both legs expired worthless, we kept the full $0.59 credit — locking in our max profit.

As we mentioned in the last example, assignment risk would have been high on our short call with around 25 days left. But for simplicity’s sake, we’re not including assignment risk here. More on that (and why I chose these strike prices) coming up next.

Choosing Deltas on Call Spreads

In options trading, delta is a key Greek — it tells us how much an option’s price will move with a $1 move in the stock. It also provides a ballpark estimate of the probability that an option will expire in the money.

This is why I always check the deltas before placing any trade. Here's the range I typically look for in a bear call spread:

- Short Call: Delta 0.30–0.40 – Decent premium, still manageable risk.

- Long Call: Delta 0.10–0.20 – Cheap protection, just far enough OTM.

- Delta Spread: 0.20–0.30 – Tight enough to stay realistic.

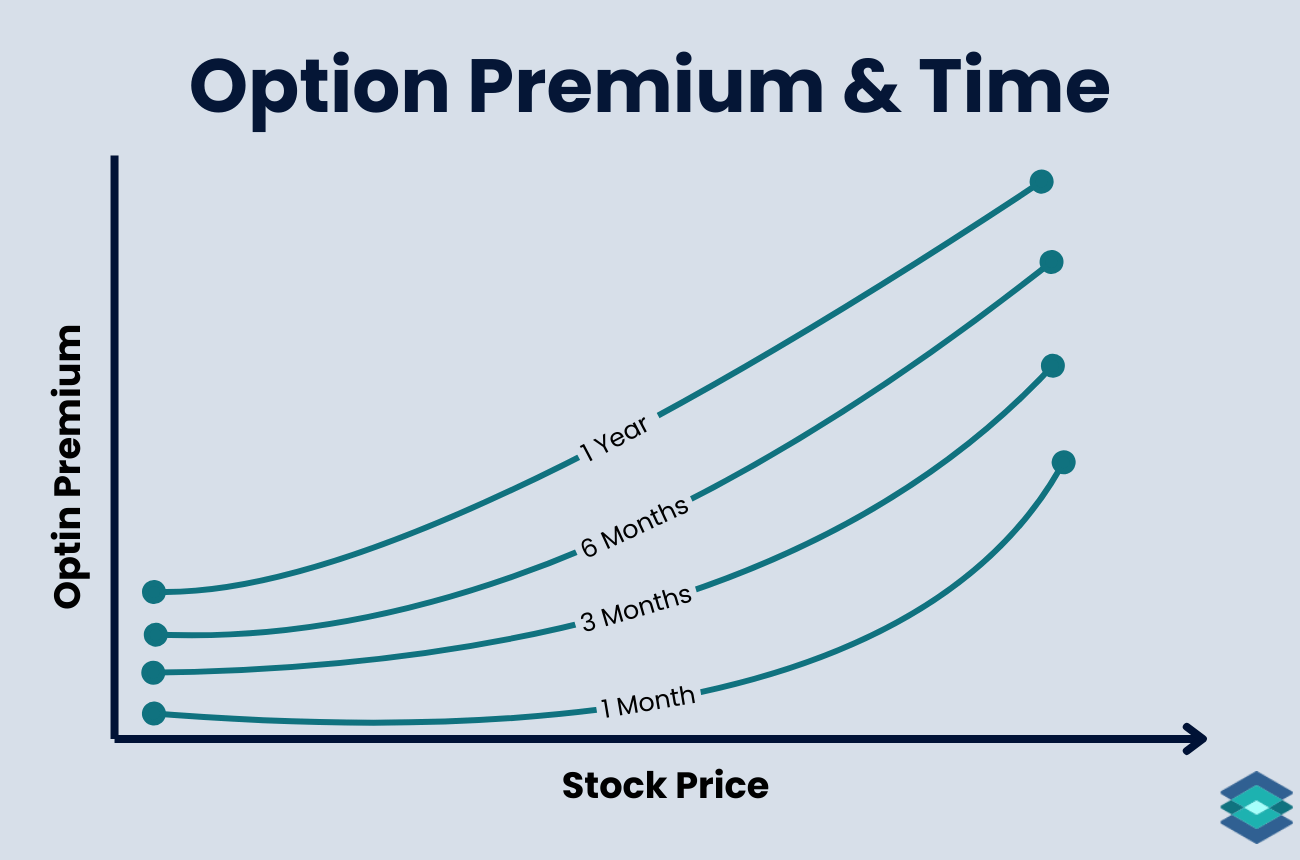

Bear Call Spreads and Time Decay

In a stable market—where the underlying isn’t making sharp moves and implied volatility stays steady—option premiums gradually erode. This steady decay benefits us as net sellers.

The closer you get to expiration, the faster that decay picks up. And since the short call holds more value than the long call, the net effect works in our favor.

.png)

Option Theta

Theta is the option Greek that reflects time decay. It tells us how much value the option is expected to lose each day. Here are a few good theta ranges to look for when setting up your short call spread:

- Short Call: Theta +0.05 to +0.15 – Main source of time decay.

- Long Call: Theta –0.02 to –0.05 – Minor drag; cheap protection.

- Net Theta: +0.03 to +0.10 – Positive overall, decays in your favor.

Bear Call Spread and Implied Volatility

When trading bear call spreads, implied volatility (IV) plays an important role. Because out of the money calls tend to have higher IV, and we’re buying the further OTM leg, the trade can be slightly disadvantaged from a volatility standpoint — especially in low IV environments.

With that said, you always want to sell options in high IV environments, typically aiming for at least 30% IV or higher.

To determine if IV is currently elevated for a particular underlying, traders often look at IV Rank — a measure of where today’s IV sits relative to the past year. An IV Rank above 30% is generally considered good for selling premium.

Bear Call: Strike Selection

The width of your spread and the premium you take in determines your total risk:

- Narrow spread: Higher probability of profit, less risk.

- Wide spread: More risk, lower probability of max profit.

Say XYZ is trading at $100. Based on my overall bearishness, here’s how I’d set up various trades:

- Slightly Bearish: Sell $105 call, buy $110 call ($5 spread), collect ~$1.00 premium. High probability of staying out of the money, max risk $400.

- Moderately Bearish: Sell $103 call, buy $110 call ($7 spread), collect ~$1.75 premium. Balanced premium and risk, max risk $525.

- Aggressively Bearish: Sell $101 call, buy $110 call ($9 spread), collect ~$2.50 premium. Larger credit due to wider spread, closer to at the money, max risk $650.

Expiration Selection

Bear call spreads are net short premium, so you want theta working for you. As we said before, time decay starts picking up around 35–45 days to expiration, so this is a great range to target.

That window gives me enough time to let theta work, but not so much time that I’m waiting forever. It also gives me flexibility to roll or adjust if things go wrong.

Bear Call Spread Setup Example

Let’s now head over to the TradingBlock dashboard to find a bear call spread that checks all the boxes we just learned about:

.png)

Managing a Bear Call Spread

Options trading isn’t passive — even with defined-risk trades like bear call spreads, you’ve got to stay engaged. Here are a few trade management tips:

Take Profits Before Expiration

If your spread is nearing max profit, exit it early. Don’t wait for expiration—if your short call finishes in the money, you could get assigned, forcing you to selling 100 shares of stock, which can be very expensive. Even if both legs are in the money, assignment/exercise fees can cost more than commissions. Close the trade and lock in the win.

Rolling Strike Prices

You’ve got flexibility if the stock moves against you:

- Roll the short call higher to reduce risk or extend the trade.

- Roll the long call higher to reduce cost if IV drops.

- Roll both legs up if the stock breaks through resistance and you want to stay in the trade.

Rolling Expirations

If you’re trade is going against you and you need more time, you can roll to a different expiration cycle. You can do this in a single 4-way trade.

3 Risks of Bear Call Spreads

Due to their defined risk nature, bear call spreads are a relatively low-risk trade - you know your maximum loss right off the bat. But there are a few other risks you should be made aware of:

1. Assignment Risk

The short call portion of the bear call spread has assignment risk when:

- The option is in the money

- The time to expiration is nearing

- There is an upcoming dividend.

The deeper a call is in the money, the less extrinsic value it has. That gives the counterparty holding the long call less reason to hang onto it—and more reason to exercise. This risk increases as the expiration date approaches.

If you’re short a slightly in the money call with 30 DTE, you’re usually safe. But fast forward to the day before expiration, and your assignment risk is very high.

Dividend risk is another factor for American-style options. Since long call holders don’t receive dividends, they’re often incentivized to exercise by or on the ex-dividend date to pick up the stock and collect the payout.

2. Implied Volatility Risk

Bear call spreads are short premium trades, meaning they benefit from higher implied volatility (IV) at entry and from a decline in IV while the position is open. But if IV rises—especially as the stock moves against you—the trade can get ugly fast.

Rising IV is like a tide that lifts all ships. It inflates the value of both calls in your spread. But since you're net short premium, and your short call is closer to the money, it usually gains value faster than your long call. That means the spread widens—and your losses accelerate.

This can happen even if the stock is moving in your favor. Volatility risk is usually highest just before the release of major economic news or earnings.

3. Liquidity Risk

Options on thinly traded stocks or ETFs can have extremely thin markets. Signs of low liquidity include:

- Wide bid/ask spreads

- Low open interest

- Low volume.

If you're trading illiquid strikes, you will likely have issues getting filled at a decent price, particularly when volatility jumps. Read more about option liquidity in our dedicated article.

Bear Call Spreads and The Greeks

In options trading, the Greeks are a set of risk metrics that help estimate how an option’s price will respond to changes in key market variables. Here are the five most important Greeks to know:

- Delta – Measures how much the option price moves relative to the underlying stock.

- Gamma – Tracks how Delta changes as the stock moves.

- Theta – Measures time decay, showing how much value the option loses daily.

- Vega – Sensitivity to implied volatility, affecting option price.

- Rho – Measures impact of interest rate changes on the option price.

And here is the relationship between bear call spreads and these Greeks

Vertical Spread Calculator

Check out our vertical spread calculator here to visualize how bear call spreads perform under different markets, conditions, and times.

⚠️Bear call spreads involve defined risk, but they still require a clear understanding of how options work. This strategy may not be suitable for all investors. Trade outcomes can be significantly impacted by commissions, fees, and slippage—none of which are reflected in the examples above. Read The Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options before trading options.

FAQ

A bear call spread is a neutral to bearish, net credit options trade. It involves selling one call and buying another further out of the money call. Both options have the same expiration and are both calls.

The maximum loss on a bear call spread is calculated as: Max Loss = Strike Width – Credit Received. This occurs if the stock finishes above the long call strike at expiration.

You profit from a bear put spread when the stock drops below the short put strike by expiration. That’s when the spread reaches max value, and you walk away with the full difference minus the initial debit paid.

You should exit a bear call spread when assignment risk is high or when you’ve captured around 80% of your max profit. At that point, the remaining reward usually isn’t worth the risk of holding.

The maximum loss on any defined-risk credit spread—like a bear call or bull put spread—is the width of the spread minus the credit received.

Both the bull call spread and bull put spread are relatively bullish strategies, but they differ in structure and risk/reward:

- Bull Call Spread: Net debit trade — you pay to enter. Profits if the stock rises above the short call strike.

- Bull Put Spread: Net credit trade — you collect premium. Profits if the stock stays above the short put.

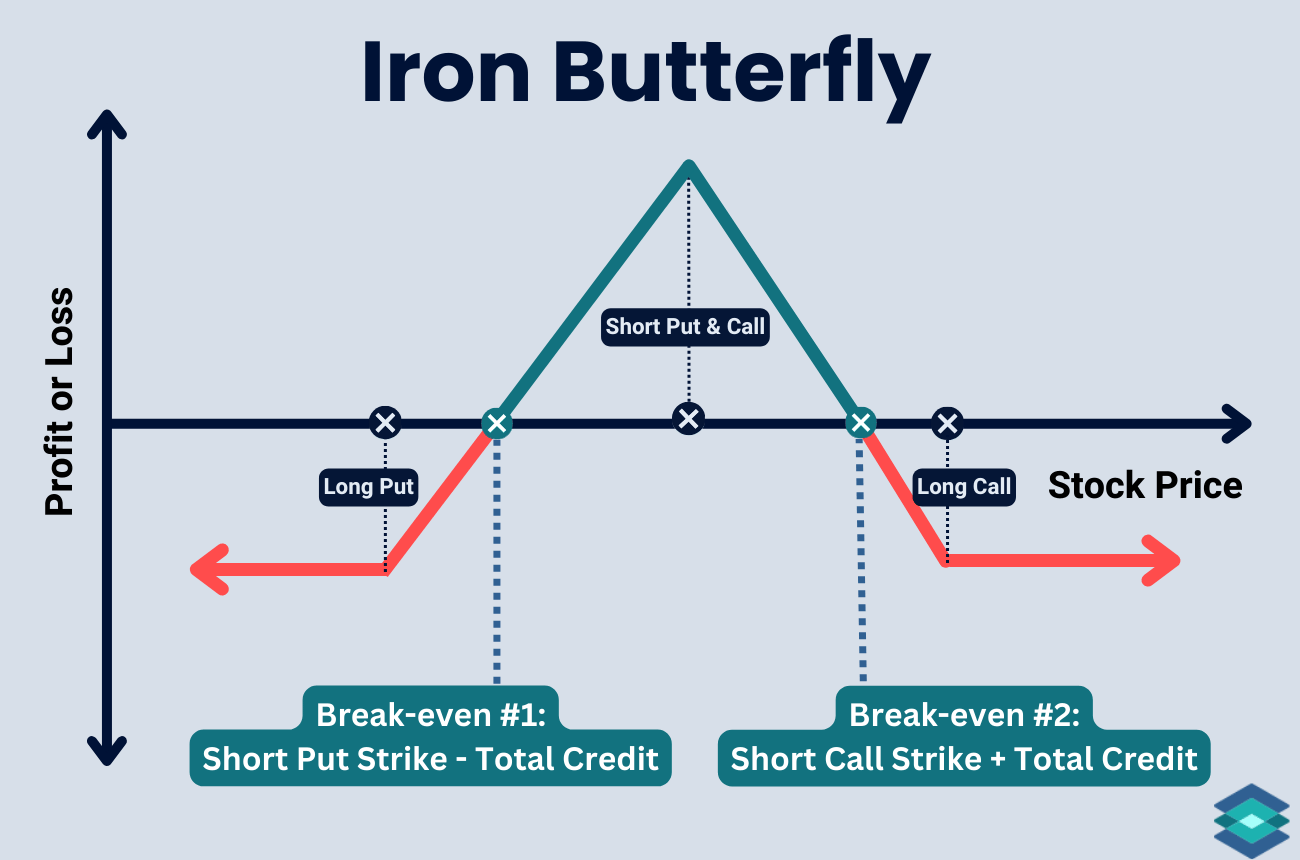

A call spread consists of selling one call and buying another further out of the money call — both with the same expiration. It’s a directional trade (bullish or bearish, depending on how it’s built).

An iron condor combines both a call spread and a put spread — selling an out of the money call spread and an out-of-the-money put spread at the same time. It’s a neutral strategy that profits when the underlying stays within a defined range.