Bull Call Spread: Complete Beginner’s Guide

The bull call spread is a defined-risk, directional trade that profits when the stock climbs higher. This vertical spread gives traders a cheaper alternative to buying a single call but also caps upside potential.

The bull call spread is a moderately bullish trade. I say moderately because if you are extremely bullish, a long call may suit you better. This vertical spread is built by buying and selling a call option simultaneously, both with the same expiration month. In this article, we'll show you how they work and when to trade them.

Highlights

🤔 New To Options? Learn The Long Call Strategy Here First!

Bull Call Spread: Trade Construction

Here are the trade components of a bull call spread:

- Buy 1 call option (closer to the money)

- Sell 1 call option (further out of the money)

- Both options are calls

- Both options are the same expiration

You can enter both legs at the same time as a single trade, or leg into it if the setup makes sense — just know there’s real risk if you enter the calls separately. Here's how this trade looks on the TradingBlock Dashboard:

.png)

The call you sell is further out of the money, which helps offset the cost of the long call and reduces the impact of time decay. It also caps your upside — but that’s the tradeoff. More on how that works in a bit.

Bull Call Spread: Payoff Profile

Let’s now explore the different trade outcomes of this debit spread.

Max Profit Zone

The max profit on a vertical call debit spread is calculated as:

Max Profit = Spread Width – Net Debit

For example, let’s say we bought the 100/110 bull call spread on ABC:

- Buy the 100 call for $6.50

- Sell the 110 call for $2.50

This is called a debit spread because we paid more than we received in credit, $4 ($400) more to be exact. Subtracting the net debit from the spread width gives us our max profit:

10 – 4 = 6 ($600)

So we’re risking $400 to make $600. When do we hit this $600? When the stock rises to $110, as seen below:

.png)

Notice that it doesn’t matter how high ABC goes — once it passes the $110 short call strike price, our max profit is capped. Every penny we gain on the 100 call is offset by a loss on the 110 short call beyond that point.

Max Loss Zone

When you're a net buyer of options, the most you can lose is the option premium paid. If you buy a call option for $3 ($300), the most you can lose is $3 ($300). The same logic applies to a bull call spread.

Let’s revisit the last trade:

- Buy the 100 call for $6.50

- Sell the 110 call for $2.50

Our net debit — or total cost — is $4.00 ($400). That’s also our max loss.

Max Loss = Net Debit Paid

If ABC finishes below the 100 strike at expiration, both calls expire worthless. We’re left with nothing — and out the $400 we paid to open the trade.

The image below highlights this defined max loss zone.

.png)

Breakeven Zone

The breakeven for a bull call spread is when the stock has risen just enough to cover the amount you paid to enter the trade. Here’s what the math looks like:

Breakeven = Long Call Strike + Net Debit Paid

Using our 100/110 bull call spread example:

- Bought the 100 call

- Net debit is $4.00

So the breakeven is:

100 + 4 = 104

That means ABC needs to close above $104 at expiration for us to start turning a profit.

If ABC closes exactly at $104, gains from the 100 call offset the initial $4 debit, and you're flat on the trade — no gain, no loss. But this presents exercise/auto-assignment risk, which we’ll cover soon.

.png)

Alright, now that we've got the profit profile down, let's explore a real-world trading example!

Trade Example: XLF Call Spread

In this example, we’re setting up a bull call spread on XLF (Financial Select Sector SPDR Fund).

We think XLF is going to rise moderately over the next month and a half. The stock is trading at $47.82 right now, and we expect it to approach 51 within the next 45 days.

Let’s jump into the TradingBlock dashboard to find two call options that fit the setup:

We chose XLF for a few reasons:

- Broad-based exposure

- Decent bid/ask spreads and low slippage

- Numerous strike prices and expirations

Trade Details

- XLF Price: 47.82

- Expiration: 45 days

- Buy 48 Call @ $1.69

- Sell 51 Call @ $0.38

- Net Debit Paid: $1.31 ($131 total)

- Breakeven Price: $48 + $1.31 = $49.31

- Max Profit: $3.00 – $1.31 = $1.69 ($169 total)

- Max Loss: $1.31 ($131 total)

As we can see, we bought a 3-point call spread for $1.31 ($131 total), which is also the most we can lose on the trade. The most we can make is the width of the spread minus the debit, or $3.00 – $1.31 = $1.69 ($169 total).

XLF Bull Call Spread: Positive Outcome

Let’s fast-forward 45 days. Bank earnings widely beat expectations, and XLF took off, closing at $53 on expiration. Let’s see how our trade did:

- XLF Price: $47.82 → $53 📈

- Expiration: 45 days → 0

- Buy 48 Call @ $1.69 → $5.00 📈

- Sell 51 Call @ $0.38 → $2.00 📈

- Final Spread Value: $3.00

.png)

Because $53 is above both strike prices (48 and 51), both calls expire in the money and have 100% intrinsic value. This means we realize maximum profit on the trade.

- We bought the 48 call, which is now worth $5.00 (intrinsic value = $53 – $48)

- We sold the 51 call, which is now worth $2.00 (intrinsic value = $53 – $51)

Because we originally paid $1.31, our final profit is:

$3.00 – $1.31 = $1.69, or $169 total per spread

XLF Bull Call Spread: Negative Outcome

Let’s fast-forward 45 days. In this trade outcome, XLF underperformed, falling from $47.82 to $44 on expiration day. Here’s how our trade performed:

- XLF Price: $47.82 → $44 📉

- Expiration: 45 days → 0

- Buy 48 Call @ $1.69 → $0.00 📉

- Sell 51 Call @ $0.38 → $0.00 📉

- Final Spread Value: $0.00

.png)

This trade started off great—but it went downhill fast. Notice how we locked in ~80% of our max profit on our spread with plenty of time until expiration. We should have closed it out at this point. In the markets, time is risk—and this example proves it.

Bull Call Spread: 3 Major Risks

The bull call spread carries far less risk than single-leg trades like long calls or short puts. However, traders should still watch out for a few key risks.

Early Assignment Risk

The short call side of a bull call spread is exposed to assignment risk. This happens when the short call is in the money—and that risk increases the closer you get to expiration.

If you’re assigned early, the fix is simple: just exercise your long call. That offsets the short stock and effectively closes the position.

The good news is that an assignment usually happens when the short call has no extrinsic value, which means your trade is likely at max profit anyway.

IV Crush

Long options benefit from high implied volatility. If the underlying asset experiences a sharp drop in volatility while you’re holding a bull call spread, the option premiums will fall—causing your position to lose value.

Vol crush tends to happen after anticipated events, like earnings announcements or major economic releases (think Fed meetings or jobs reports).

Liquidity Risk

Options on thinly traded stocks or ETFs can have extremely thin markets. Signs of low liquidity include:

- Wide bid/ask spreads

- Low open interest

- Low volume.

If you're trading illiquid strikes, you will likely have issues getting filled at a decent price, particularly when volatility jumps. Read more about option liquidity in our dedicated article.

The last risk deserves a section all of its own: time decay.

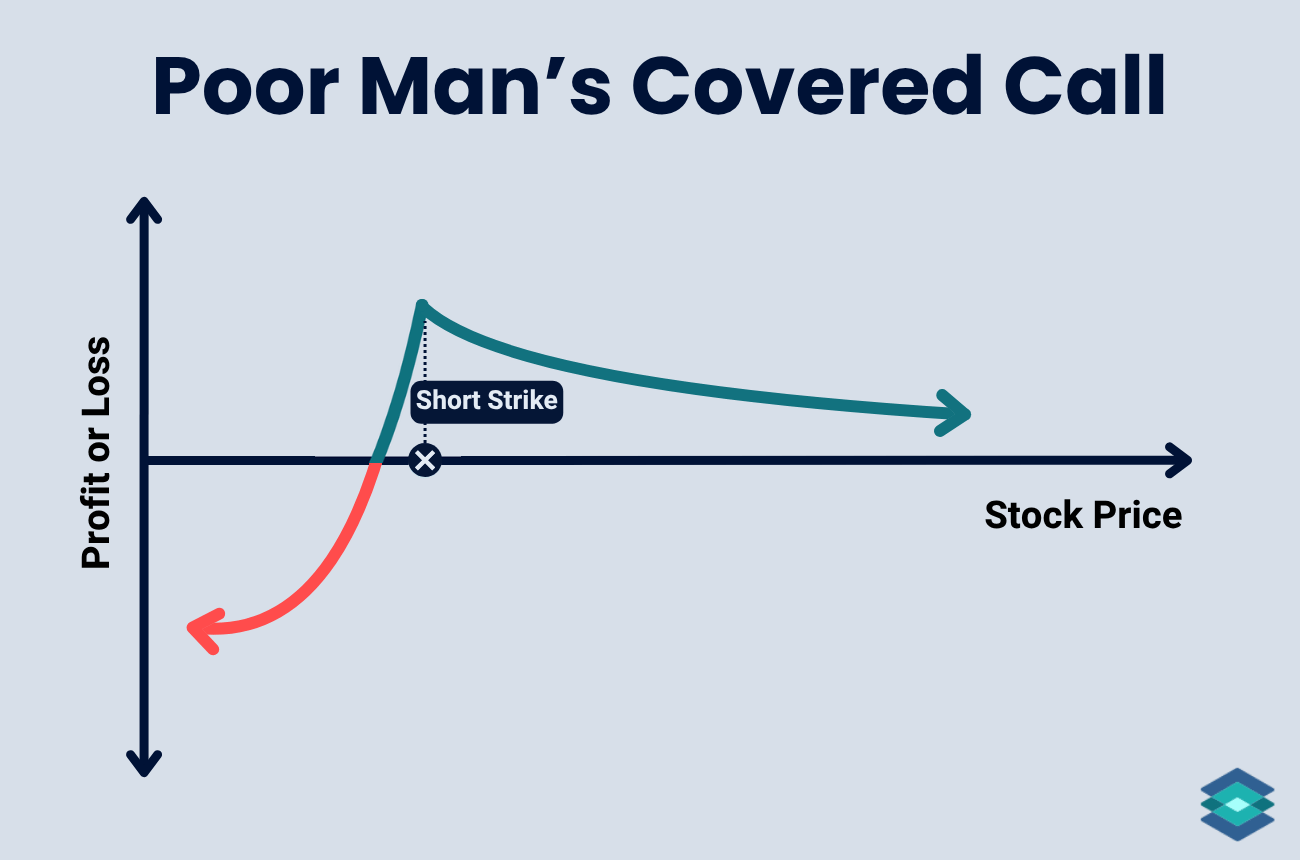

Bull Call Spreads and Time Decay

In a constant environment, meaning the stock price and implied volatility stay the same, option contracts shed value every day. That’s great if you’re net short options.

But a bull call spread is a net debit position, which means you're long premium overall. And that makes you vulnerable to time decay. If the stock doesn’t move quickly enough, your spread will shed value over time—whether you're right on direction or not.

.png)

It’s worth noting: time decay on a bull call spread is less severe than on a single long call.

- Long Call: This leg loses value each day—even if the stock doesn’t move. The further out of the money it is, the faster it decays early on.

- Short Call: This leg helps offset that decay. As time passes, the short call loses value (which works in your favor), but it usually has less premium to begin with.

Bull Call Spreads and Implied Volatility

Bull call spreads are net debit positions, benefiting from rising implied volatility (IV). When IV jumps, so does the value of all options—calls and puts alike.

Here’s how IV impacts a bull call spread:

- If IV rises after entry: Both legs gain value, but your long call usually gains more than your short call loses.

- If IV drops: Both legs lose value, but the long call takes the bigger hit. Your spread shrinks, and you can lose money even if the stock moves in your favor.

Bull call spreads work best when IV is steady or rising after entry. If you're putting the trade on ahead of a known event—like earnings—be careful. IV crush is real, and it can wreck your trade if the move doesn’t come fast and strong.

Strike Price and Expiration Selection

Two important questions to ask yourself before putting on any options trade are:

- How confident am I that the stock will move up — and how far?

- How long am I willing to wait for that move to happen?

Choosing the appropriate strike prices and expiration dates is key when trading a vertical spread. Let’s start with strike price selection.

Bull Call: Strike Selection

Option spreads give traders a ton of flexibility. You can tailor a bull call spread to fit all kinds of market outlooks. Here are two rules of thumb for strike selection:

- Narrow spread: Lower cost, lower max profit, higher probability of max profit.

- Wide spread: Higher cost, higher max profit, lower probability of max profit.

For example, let’s say ABC is trading at $490. Here are a few ways to build the trade based on your level of bullishness:

- Slightly Bullish: Buy $500 call, sell $503 call ($5 spread). Low cost, high probability of profit.

- Moderately Bullish: Buy $500 call, sell $510 call ($10 spread). Balanced cost and reward.

- Aggressively Bullish: Buy $500 call, sell $520 call ($20 spread). High cost, big profit potential.

The wider the spread, the more reward you’re going after — but these lower the probability of success, and make you take on more risk.

Narrower spreads come with higher probability, but smaller payouts. Just don’t go too narrow, especially with cheap spreads. If you’re buying something like a 100/101 call spread for $0.40, your odds of success may be high, but the payoff is tiny. Commissions on narrow spreads will also eat into your profits.

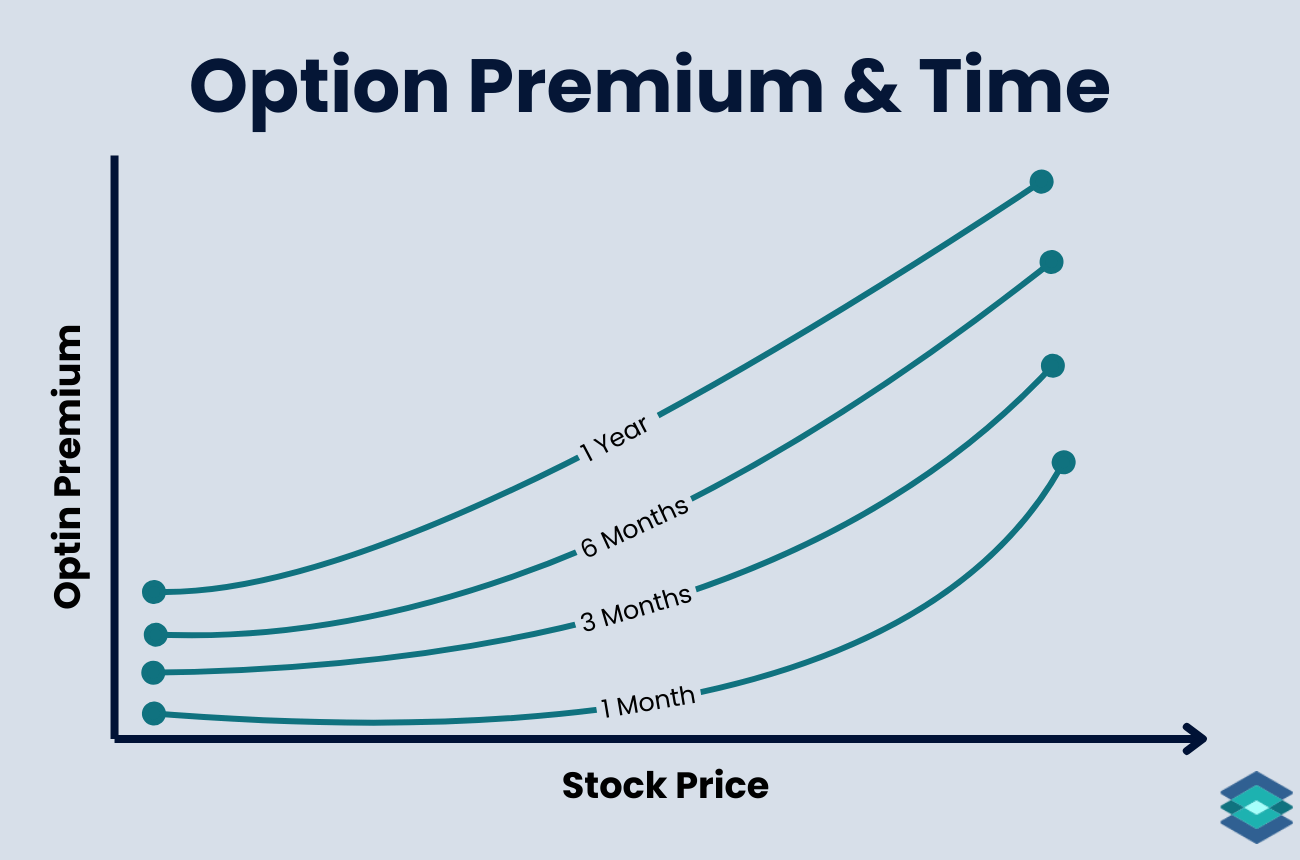

Expiration Selection

When you’re net long options, time is not on your side. That’s because with each passing day, time decay—or theta—eats away at the value of your long option.

Because of this, a great entry point for vertical spreads is typically around one to two months until expiration. Of course, this rule has a million exceptions, but that’s the timeframe I aim for. You’re probably overpaying for the long option if you’re going out any longer than that.

This window also gives you enough time to adjust or exit the trade if the market moves against you. You won't have time to adjust or roll your strikes if you put a debit spread on with only 4 days to expiration (DTE)

Delta Selection

In options trading, delta is one of the key option Greeks — it tells us how much the price of an option is expected to change with a $1 move in the underlying. Delta also gives us a rough estimate of the probability that an option will expire in the money.

That’s why I always look closely at the deltas in my bull call spread before sending the order. Here are the delta ranges I tend to target for the long and short calls in a typical bull call spread:

- Long Call: Delta 0.50–0.60 – Higher probability; decent stock sensitivity.

- Short Call: Delta 0.20–0.35 – Less likely to finish ITM.

- Delta Spread: 0.30–0.40 – Wide enough to profit, narrow enough to stay realistic.

Bull Call Spread: Options Chain

Let’s take everything we just learned and apply it to a real-world options chain on the TradingBlock dashboard. We’re looking at calls on SMH (VanEck Semiconductor ETF) that expire in 46 days.

I’d probably buy the 207.50/217.50 call spread. Here’s why:

Managing a Bull Call Spread

Options trading is not passive investing; the same is true for defined-risk trades like debit spreads.

Take Profits Before Expiration

If your bull call spread is at or nearing max profit, close the trade early. If you hold through expiration and your long call finishes in the money, it may be automatically exercised, forcing you to buy 100 shares at the strike price. If your short call expires out of the money, you’re left with a long stock position you probably didn’t want.

If both options are in the money, you’ll be exercised and assigned—same outcome, but with extra fees that are usually higher than just closing the spread outright. Save yourself the hassle and lock in the win.

Rolling Strike Prices

You have a lot of flexibility in bull call spreads when rolling the strike prices.

- Roll the short leg to a higher strike to increase max profit (Vertical Spread)

- Roll the long leg closer to the money to regain delta if the stock pulls back (Vertical Spread)

- Roll both legs up or down together to reposition the entire trade (4-Way Vertical Spread)

Rolling Expirations

Not all trades are going to go your way. If you need more time on your bull call spread, consider rolling it out to a later expiration. Just make sure you roll both legs at the same time—if you only roll one leg, you could end up exposed to considerable downside risk. This can be accomplished in a 4-way trade.

Bull Call Spreads and The Greeks

In options trading, the Greeks are a series of risk tools that hint at the future price of an option based on changes in different variables. Here are the 5 most important Greeks to know:

- Delta – Measures how much the option price moves relative to the underlying stock.

- Gamma – Tracks how Delta changes as the stock moves.

- Theta – Measures time decay, showing how much value the option loses daily.

- Vega – Sensitivity to implied volatility, affecting option price.

- Rho – Measures impact of interest rate changes on the option price.

And here is the relationship between bull call spreads and these Greeks:

Vertical Spread Calculator

Check out our vertical spread calculator here to visualize how bull call spreads perform under different markets, conditions, and times.

⚠️Bull call spreads involve defined risk, but they still require a clear understanding of how options work. This strategy may not be suitable for all investors. Trade outcomes can be significantly impacted by commissions, fees, and slippage—none of which are reflected in the examples above. Read The Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options before trading options.

FAQ

A bull call spread is a bullish options trade made up of buying one call at a lower strike price and selling another call at a higher strike. Both options must be in the same expiration cycle.

Bull call spread trade success depends on how the trade is constructed. Wide spreads bought for a cheap debit have lower odds of profit, while narrower spreads bought for more premium typically have a higher probability of success.

The bull call spread is a net debit trade — meaning you’re exposed to time decay (theta). As time passes, assuming the stock price and implied volatility stay the same, your long call will lose value faster than your short call gains.

The best time to exit is when you’ve captured about 80% of the max profit. The last few days are the most inefficient — time decay accelerates, and the remaining reward isn’t usually worth the added risk.

There are four main types of vertical spreads: the bull call spread, bear call spread, bull put spread, and bear put spread. Each one is built using two options of the same type (calls or puts), same expiration, but different strike prices — and each targets a specific directional outlook.

With vertical spreads, you’re exposed to implied volatility and time decay. The most you can lose is the net debit paid (if it’s a debit spread) or the difference between strike prices minus the credit received (if it’s a credit spread). Either way, your max loss is defined upfront.

Yes — vertical spreads are one of the most best ways to trade directionally. They let you use leverage with limited risk, while also reducing the negative impact of time decay and volatility swings, compared to buying naked options.